Listening

Neuroscience reveals that each brain has unique pathways for listening. An essay on “listening” and why it’s changing

Four years ago, I worked on a project designing programs for children with hearing disabilities. Through that experience, I realized I knew very little about "listening." This widen a journey to creating a platform for sharing my discoveries and helping others access a deeper, more transformative way of listening.

What follows is an essay on the evolving nature of listening and why it’s changing? You will learn about the tremendous work of Neuroscientist and Author Dawna Markova.

Vertebral body and disc morphometry of spinal radiograph

Quick Ai Summary Of Sections

The Essay:

Stop Talking To Me And Listen

Most nights my body allows me to sleep well but this time, my body is irritated. I’m not usually up so early, but out of desperation, I direct my alertness towards responding to my emails. One lies patiently for me to read from a prospective client eager to start a strength program. She shares her experience of being sexually assaulted and her desire to reconnect with her body. Unlike most people, she isn’t concerned about her aesthetics nor her body fat. She wants to feel strong again, confident again, and seen again. Never have I felt so inadequate to help. Frustrated and uncertain, I scheduled a consultation call with her, knowing full well that all I could do was listen. No knowledge of biomechanics, force production, or muscle fibre contraction could have prepared me to support someone who had experienced such trauma. For survivors of sexual assault, the discomfort of moving their bodies can be more than just physical; they may hold an intrinsic belief that something is wrong with them, that they are irreparable beyond repair. In a world where everyone seems to have something to say, the value of truly listening often gets lost. Listening was my only resource. The strength it takes to raise your hand and admit that you need help is significant, but the strength required to refuse to let a traumatic experience define you is even more profound. What makes that possible is this ability to listen to ourselves.

What exactly is listening? Unfortunately, there isn't a real consensus about what "listening" is, in many scientific fields. So listening has become an understanding that has focused primarily on hearing or comprehending language. Motivating a market to portray listening as the performance of hearing dialogue and expressing that you've received it. Even the concept of listening to oneself is dominated by the self-help industry—a sector driven by trends rather than peer-reviewed science, which I will admit has its own flaws. The expectation that is placed on individuals is to sift through information to discern what is credible. Over the years, the self-help industry has reshaped what it means to have a dialogue with oneself. Creating new identities to formulate around. Before understanding the importance of identity in relation to oneself or self-dialogue, we must first explore its role in social psychology. Identity can be construed as the distinctive characteristic shared by members of a social category or group. The most important relationship you will ever have is with yourself. Your emotional welfare depends on how you feel about yourself, shaped by the relationship you have within yourself. Thus, a loss of identity and sense of self can cause us to seek our self-worth from others. The self-help industry often cultivates the perception that a healthy internal dialogue must always be positive, avoiding negative self-thoughts and affirming one's values. The issue with accepting a narrative like this, is essentially it dissolves self-conversation without the "nasty parts," leading to the belief that something is wrong with us if we fail to meet these standards. This mindset stirs up the idea that self-acceptance is conditional and contingent on us maintaining a positive relationship with oneself. When we internalize these concepts, it becomes difficult to separate our personal mindset from the philosophy being stitched to our identity.

A fixation on a constant state distracts from feeling our reality and being able to process and interrogate our plastic and unhealed feelings that we may not even have words for. Instead, we praise messages that comfort us and that caress us, suggesting that we are worthy of being human, but only without the "nasty parts." This creates the perception that all negative thoughts are internal ones and that they can be controlled. However, a research paper by Dr. Benjamin Alderson-Day and his colleagues highlight a different way of looking at these negative or intrusive thoughts, to have a different reality for people with schizophrenia—a mental disorder characterized by hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thinking. Their study, "Susceptibility to Auditory Hallucinations is Associated with Spontaneous but Not Directed Modulation of Top-Down Expectations for Speech," shows that individuals with schizophrenia hear voices differently due to their auditory receptors responding differently to sounds. To understand why this is important to their thoughts, we need to understand how our brain processes sound. Our brain has an incredible capacity to process sensory information like sound. In the case of people with schizophrenia their auditory receptors respond to different types of sounds. Which means, they don’t process sounds the same way but there is no actual damage to their brain to cause this change. Including the way they hear voices inside their head. What is described as auditory hallucination or “hearing voices”. When we are listening to ourselves a set of neurons, responsible for sending and receiving neurotransmitters—chemicals that carry information between brain cells. fire response to our auditory cortex, the part of the brain that processes auditory information, allowing our brain to process the sound we hear as our own. What we learn through this study is that those with schizophrenia hear sound as what we perceive to be them talking to themselves (their-voice), by firing neurons to the auditory cortex that directs their brain connection to hear the voice as being outside of them. Which means a voice that isn’t familiar to them, can be associated outside of their own registry of their voice. This suggests that their negative thoughts or self-talk is not always within their control. Naturally those who have schizophrenia are more animated in conversation with themself not because they are dangerous or violent but rather their brain communicates their voice in a deceptive way. Therefore the negative talks they have with themselves are often more aggressive and directed to thin air or to nobody because their voice is not theirs’. Oftentimes this forces them to be harmed more or less by others and become victims because of this misunderstanding. Knowledge from research like this helps us understand why embracing our "nasty parts" can foster compassion and understanding. These difficult aspects are part of our reality and help us learn. If we deny them, we lose what they can teach us about ourselves.

The central concern of my writing is not to advocate for a practice around negative thoughts nor reinforcing negative language to self. Instead the problem is when we accept a single conception about a human experience or process like listening, we begin to believe it is one dimensional. Instead of looking at it like our spine, it is multidimensional. Our spine is often categorized as fragile and that we should stand up straight and pull our shoulders back for better posture. We neglect that the spine was not meant to be a straight vertical figure and that a healthy spine has an “s” shape curve for a reason. A true neutral spine has some degree of roundness at the upper back allowing the scapula to move freely so that it can sit on our rib cage. To create an optimal guiding and function but if we constantly absorb the idea that our backs need to be straight we condition ourselves to limit movement in the scapula and that compromises shoulder mobility over time. The curvature of our spine has a responsibility to make us stronger individuals and more reluctant to be capable of moving through the world in a certain way. The spine that maintains our body and the connection to our body isn’t straight, similar to how we perceive listening. It isn’t just hearing, it’s multidimensional. It is a state of experiencing and connecting and relating to ourselves and others that is fundamental to our being. For the purpose of this essay I will use the definition of listening by Wolvin and Coakley, as a process. They emphasize that listening is an active process of selecting, attending to, understanding and remembering auditory messages. Like the communication process, listening has cognitive, behavioral, and relational elements and doesn’t unfold in a linear, step-by-step fashion. While there is no consensus about what listening is; one theme remains abundantly consistent: listening is essential to our wellbeing and every aspect of it. Our relationship and discernment of ourselves depend on it. My hope, through this essay, is that you will learn how the western prevalent misconceptions about listening ruins the process in how we relate to one another and why language is failing us to overcome it.

Me : As somebody who’s already worked in the accessibility space. Also has worked with sound before, it’s very easy for people to kind of get confused, or at least not have a real guardrail or understanding of basically what listening is? So I’m curious from a learning perspective, but also from an accessibility perspective, you know how, or what either definitions or ideas or frameworks do you guys use when you guys are thinking about or trying to understand listening?

Colin: I mean, I don’t think I can define listening [laugh] I know what, I’d love to be able to, but I can’t, at least in this time in my life, I can’t speak to what is listening from a disability perspective in terms of being hard of hearing or deaf or things like that. I mean I guess what’s interesting to me about listening in this context is that there are different ways of listening and I don’t know if I’m pointing out something that is terribly obvious but we listen differently and at different times, different ways and in different settings. So there are things I think about with listening, culturally.

Listening and the Body

South Omo Mursi women - photograph with their children

MRI scan showing a fetus during the 36th week of pregnancy. Babies are born with 100 billion neurons

Our bodies are in constant motion, much like the surface of an ocean. This movement, called oscillation, refers to the movement of back and forth at a regular speed, like the beating of the heart, the inhale and exhale of lungs, the contraction and release of muscle fibers, the rapid alternation of electrical and chemical stimulation in a neuron and the squeeze and release of the gut (peristalsis). Our body lives in a constant oscillatory symphony of movement. All that oscillating creates a kind of hovering around certain metabolic set points such as our body temperature, our oxygen levels, often called homeostasis. A common misconception with listening, is that listening is solely tied to having functioning hearing and that any obstruction can limit this capacity for listening. However, research has shown that listening involves much more than just the mechanics of hearing. For instance, consider the Mursi women of the South Omo, which lie between the mountainous center of Ethiopia and the highlands of Kenya, home to some of Africa’s most culturally diverse ethnic groups. These women wear lip and ear plates that stretch their skin away from their ear openings. Despite this apparent "obstruction," they demonstrate highly synchronized and fluid conversations. Mursi women are the last women in the world to wear lip plates and ear plates, some plates having greater weight to reflect status on their ear. No anthropologist has been able to explain with clarity the origins or function of this mutilation in ear, some historians say that it was a way to deter slavers to protect women from being enslaved. When Sebastiao Salgado, Brazilian social documentary photographer and photojournalist, visited them in early 2007, he was stunned to discover the accuracy of their listening and exchange of jokes. The fluidity of conversations between different genders and members of the tribe, each moment forced him to be more an observer and at awe with the obstruction to their listening. What Salgado and the western society overlook about our listening process, is not what happens to our ear but what happens inside our ear that determines our listening. Oscillation, as a pattern of movement, is vital to how we connect to our bodies and listen. A fetus begins listening inside the womb even before it develops the capacity for conscious processing of what it is hearing, using oscillatory patterns and reverberations to connect with the mother. What is really unique is that a fetus, an offspring in the stages of prenatal development that follow the embryo stage (in humans taken as beginning eight weeks after conception), doesn’t receive their hearing capabilities until approximately seven weeks when they develop their cranial nerves, the nerves that emerge directly from the brain (including the brainstem), of which there are conventionally considered twelve pairs, that relay information between the brain and parts of the body, to regions of hearing and other functions.[1] The brain is the only organ not fully formed at birth. Only its basic structures are intact. Babies are born with about 100 billion brain cells and on average their brain weighs 12 ounces at birth, about 25 percent of its full size. The brain is already a functioning organ prior to birth and so is our listening. As the fetus develops it is engaged in a different type of listening for the first three weeks, which images are able to pick up through frequencies, as the fetus is connected to its environment. Studies by Kathleen Wermke on pre-speech development demonstrate that babies are highly attuned to frequencies in the womb, which helps them imprint the dialect of their mother even before birth. They are able to memorize auditory stimuli from the external world by the last trimester of pregnancy, with a particular sensitivity to pitch and melody contour in language. Babies keep a working memory of the changes based on prosodic information, which means the way a voice rises and falls during speech. Much of Wermke's work is determining a threshold for what goes wrong in infants' process for language acquisition. Crying is a strong indicator of whether a baby will learn language. It plays a far more pivotal role in human development than we often realize. Not only does it serve as a means for newborns to signal their needs, but it is also an essential part of learning how to control breath and vocal cords—crucial skills for producing speech as they grow. This uniquely human sound, rooted in our earliest experience, has an additive quality: it fundamentally shapes our capacity for communication and connection. This additive nature of crying extends beyond development and finds resonance in culture and art. A vivid example is found in a celebrated song from the late 1990s. In 1998, Aaliyah, a rising R&B artist, gathered with her team at The Village Studio in West LA to record what would become a hit track. At the heart of this song’s infectious chorus was a delicate “baby cooing”—a soft, plaintive cry. Decades later, journalist Jeremy D. Larson would attempt to trace the origins of the baby’s voice sampled for this song, only to discover that its source remains shrouded in mystery. Yet critics and fans alike acknowledge that the baby’s cry is central to the song's emotional impact; without it, the music simply wouldn't have the same effect. The reason for this significance lies in the deep-rooted connection between human emotion and the sound of crying. Research shows that cries are far more sophisticated than they seem. Not only do babies develop the remarkable ability to isolate their own cries from others, but their early sensitivity to such frequencies suggests that listening is more than a passive sensory act—it is the bedrock of social connection. From their very first months, infants rely on crying to communicate, and how those cries are understood can shape everything from parental bonding to neurodevelopment. Considering that infants cry on average between 1.5 and 3h per day [4], the impact of infant crying on parents can vary and can be draining between experiences of anxiety, depression, helplessness, anger, and frustration in response to infant crying. For years, it was believed that only mothers possessed an intuitive ability to decode these cries. However, research by Martin GB and Clark RD, along with seminal work by Sagi A and Hoffman ML in 1976, demonstrated that babies themselves respond empathetically to the cries of others. This profound sensitivity highlights the communal and emotional dimensions of crying, tying together its biological, psychological, and cultural significance. Building on their work, Martin GB and Clark RD conducted an intriguing experiment inspired by Hoffman’s earlier work. They played recordings of babies’ own cries to them, finding that even newborns, though disoriented at first, did not cry in response to hearing themselves. This discovery is striking because, at such an early stage of development, infants’ brains—particularly the left hemisphere, responsible for language and analytical processing—are not fully developed. Instead, the right hemisphere, which grows rapidly in the fetus and is adept at synthesizing sensory information, dominates early thinking. As neuropsychologist Elkhonon Goldberg suggests, this right-brained integration allows babies to form a primitive sense of self through bodily sensations and responses long before language or advanced auditory analysis emerge.

In essence, our ability to listen is intricately woven into the very fabric of our early development. Babies may not “analyze” sound as we do, but their bodies and brains are attuned to oscillations and sensations, beginning the lifelong process of connecting with—and interpreting—the world through sound. These insights reveal that the simple sound of a baby’s cry is anything but simple. From shaping language and communication to evoking deep emotional responses in art and music, crying is a powerful thread that connects us biologically, socially, and culturally. At its core, crying reminds us that listening is not merely hearing—it is a deeply embodied, developmental process that begins before words and continues shaping our sense of self and connection through life.

Listening and Performance

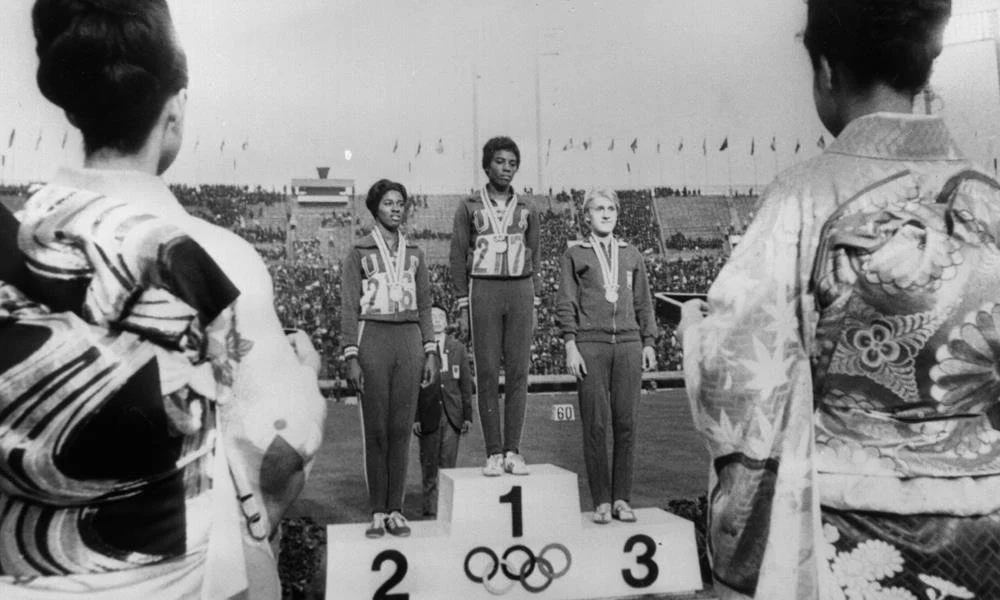

Wyomia Tyus - 1964 Tokyo Olympics podium

When we perform listening there’s an image in mine that is easy for us to see, an image of us listening tentatively to words, being present and undistracted. We assume that image is similar for others too, we control our environment and the sounds surrounding it. Wyomia Tyus, born August 29, 1945 in Griffin Georgia, a 19-year-old sprinter who competed in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, offers another perspective on listening and its misunderstanding towards its performance to the human body. She wasn't expected to win, but she did. In 11.04 seconds in the 100 meters, she had run the second fastest 100m in Olympic history. Four years prior to her race, she had lost her father to an illness, that forced her to be mute and shorten her conversations to one word answers, but her coach Ed Temple, Head Women's Track and Field Coach at Nashville's Tennessee State University, trusted in her abilities and work with her to prove she was capable of making her father proud. Her success wasn't due to her fast reaction time at the start of her run. Instead, it came from a deeper understanding of her body's movements and how to regulate her nerves. Tyus's ability to "listen" to her body and respond effectively, despite external pressures, was key. When runners place their foot on the starting block it provides a solid surface to push off the leg and generate power. The mechanics underline the force of movement to have a good start off the block. Requires the least amount of ground contact time to create the least amount of air time( picking up their foot) in the first 20 meters. A false start, in track field, is when an athlete leaves the starting point block or before a pistol fires after the set. In today’s world an electronic starting block can determine a false start by using a false start detection apparatus that is from World Athletics, the international governing body for the sport of athletics, covering track and field. Electronic blocks determine a false start by using reaction time. An athlete with a reaction time of less than one-tenth of a second will be deemed a false start and an acoustic signal will emit to at least the start team(a team monitoring starts). An interesting fact about false start, is the one tenth of a second range is based on an assumed minimum auditory reaction, this rule means once an athlete’s brain processes the sound of the gun their body can’t react faster than 100 milliseconds to push off the block. World Athletics maintains this rule even though their own research shows that auditory reaction can be as fast as 80 millisecond. Most athletes don’t train to hear the gun as a way to improve their start time or reaction, instead they focus on relaxing their body. As track and field running is a jammed packed pressure cooker of nerves and ideally the best way to prevail, isn’t to control them but to relax them. Elite athletes don't train to control their environment; instead, they work within their discomfort. Listening should be approached the same way—by accepting imperfection and discomfort, rather than striving to control them. Athletes work through their nerves and conditions and for good reasons, as I explained the goal of the runner is to spend less time on the ground, but exactly how is that achieved? By turning on and off their nerves. When we are using our muscles with the aim of producing power and speed it is a delicate balancing act. In order to move fast we contract our muscles faster, this is done by muscle fibers, inside a myofibril, a very fine contractile fibers, groups of which extend in parallel columns along the length of striated muscle fibers are sarcomeres. A sarcomere is basically the smallest functioning unit of muscle. Inside are these thick filaments called myosin and a second component called actin, which is a thin filament, muscle contraction occurs when myosin pulls on the actin towards the center, which shortens your muscle to create the contraction from the signal of the nerve. But as the speed of the muscle contraction increases the number of myosin motors that can pull the actin decreases. So why does this matter in running? Well, the more myosin motors you have working together at the same time, the more load your muscles can handle at that speed. While the goal is speed we still need power in order to stride further, this is accomplished by working to improve the efficiency of how we use our muscles force. Athletes have a push and pull dynamic where they need to release or relax muscles that they don’t need to be firing as they make contact with the ground and into the air. Elite racers have mental markers for every second, every distance they run, with their own set performance. Just as elite racers intentionally expose themselves to discomfort—pushing past pain, fatigue, and imperfect conditions to ultimately grow stronger and more resilient—there are powerful lessons for how we approach other skillsets, such as listening. In athletics, coaches like Edrick Floreal encourage athletes to embrace moments of difficulty, arguing that it’s exactly in those micro-moments of adversity that adaptation and real progress occur. Similarly, when it comes to listening, we’ve been taught to create ideal environments: to speak clearly, to avoid distractions and to maintain eye contact. We are taught to be mindful of external discomfort as a way to better our listening experiences.

However, if the best athletes grow not because of perfect conditions but because they push through imperfection, then perhaps we should rethink our approach to listening. Much of the technology we use for listening, our headphones, our apps for consuming audio, is focused on perfecting our imperfections for listening but, real growth may happen when we allow ourselves to experience the discomfort, the distractions, and the imperfections of true, attentive listening.

Me: Emotions are in spectrum and I’m just wondering if there are moments that you have where you felt like, yea I’m not at the best place right now mentally, emotionally whatever it maybe and I still need to listen to you? Has that ever been something you look at as also being a good listener?

Danielle: This is something I struggle with, it has happened a few times and it depends very much on the context. So now I’m thinking about group settings classes or work, where it’s not necessarily appropriate to say this thing just happened. I don't necessarily have the capacity to fully listen but I’m going to try, umm and now I've forgotten the question, can you remind me?

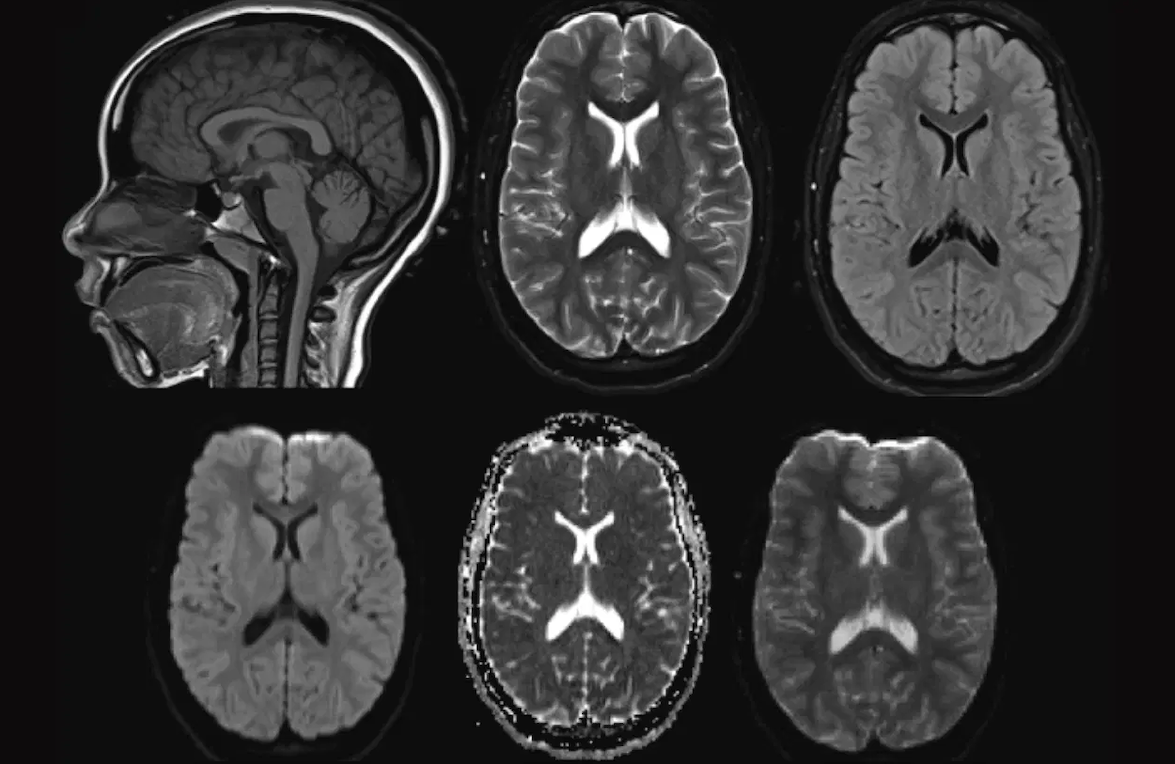

Just as elite athletes willfully expose themselves to stress—learning to thrive amidst fatigue and imperfect conditions—so too must we reconsider how we approach skill-building in other areas of life, especially listening. This becomes even more apparent in difficult conversations. When someone gets louder or more emotional, it usually signals they don’t feel heard—a moment that triggers deeper, instinctive reactions from the brain, making us feel threatened or unsafe in the exchange. The discussion quickly becomes less about the content and more about the pain of feeling disconnected. In these moments, our impulse is often to withdraw or to try and restore order to the conversation, seeking comfort. But, much like the athlete who chooses to remain in the discomfort of fatigue for the sake of growth, the true listener willingly stays present in these imperfect, chaotic, and challenging situations. Inside the brain, something transformational occurs as we sit with the discomfort, when we choose to stay in an imperfect conversation. It can create a bonding process in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), which regulates motivation and emotional responses. The discomfort we experience while listening can strengthen our connections with others, allowing us to be more vulnerable and intrepid. This is an area that is part of the brain circuitry that is critically involved formulating an addiction. But also a connection with someone else, especially the individual we are having that difficult interaction with. Allowing us to be comfortable with that person in order to create a stronger connection. In a male’s brain Vasopressin and in a female brain often Oxytocin, a hormone distinct molecules; these peptides and their receptors [OT receptor (OTR) and V1a receptor (V1aR)] are released in ventral pallidum, a component of the limbic loop of the basal ganglia, a pathway involved in the regulation of motivation, behaviour, and emotions, both in males and females. As we navigate an imperfect conversation's ups and downs, and listen. These molecules let us feel more safe by regulating how we are experiencing that conversation through our brain and we begin to understand the other individual in a way we haven’t before. This allows us to listen more openly within more difficult conversations not only with that individual but also with others, we expand our listening in conversations. We start to recognize and understand our vulnerabilities, just like athletes we hone in on the moment. Being aware of and acknowledging them as a source of strength. It allows us to move through the body, be at conscious choice, and create from our vulnerabilities. Vulnerability is not weakness, because vulnerability is about uncertainty, risk and emotional exposure. Vulnerability is daring and our nervous system doesn’t like it. It likes what we can predict because it will be more adapted to respond. But just like athletes, if we stay at that level our body can’t respond to new stressors. As our nervous system is much more dominant and in control than our muscles. This is why athletes engage in meticulous and rigorous boring steps to penetrate their nerve reflexes, stacking them on top of each other, to help them transform their nervous system. Every aspect of skill we try to improve requires hard work and listening should not be any exception. The problem is we can’t build a system around listening with the same metrics as running 100 meters. The reliance to focus on listening from a conscious point of skill, makes our nervous system become an afterthought and invisible to our standards for what we identify as good listening. Learning to listen well begins with understanding what type of listener you are and that starts with your nervous system. We can train listening to be instinctual just like how elite athletes train their muscles through a diversity of exposures. Whereas we can train through sound, with different frequencies for our brain to be more fluid in connecting. As sound influences us in so many unimaginable ways, the flow of running water, birds on the morning street and soft rumbling winds create a typically gentle and rhythmic soothing for us. This is because our brains are wired to recognize these sounds as safe. It is ecology in motion. It is nature making itself heard. What isn’t safe to our brains are sounds we can’t hear, like silence. Some silence doesn't have frequency and this triggers our nervous system. This also triggers our auditory cortex too, as I learned working with born deaf children. Losing the capacity to hear doesn’t mean you’re not listening. Hearing in silence actually activates the auditory cortex, showing that the brain responds to the absence of sound much like it does to actual sounds. This heightened alertness may explain initial unease but also stimulates beneficial processes such as neurogenesis (the growth of new brain cells). Your nervous system is always listening, because it is the system that is responsible for keeping you alive and the communication within your body. It doesn’t understand a verbal language and therefore we have to learn to speak the language of the nervous system. Which is somatics, internal physical sensations, perceptions, and experiences of the body, an embodiment, in order to actually make change to it. We have to build our capacity within triggering our discomfort to our nerves. When it comes to doing this with our listening this appears confusing if we’re focusing on listening from primary being about hearing sound. Instead of focusing on vulnerability, something that has an energetic charge to it and if our nervous system doesn’t have an experience or reference point of that yet while learning, it overwhelms our system and body to get out. When I say “vulnerability is energy”, it might be hard to resonate or understand what that actually means, but in order to know how? We have to look at our brain through an MRI machine. The way an MRI works is by using a powerful magnetic field and radio waves to generate images of the body and of the brain.This machine uses these powerful magnets that align the protons in our body’s water molecules. It then sends radio waves through the body, which knock protons out of alignment. When the radio waves are turned off, the protons realign with the magnetic field releasing energy in the process, the energy is detected by the machine and a computer then processes that energy into a detailed image. When our brain experiences vulnerability we can see brain activity in the amygdala, a processing center for emotions, like fear. When our body experiences vulnerability it produces more oxygen. This is to ensure that oxygen is available to support heightened activity levels, for releasing energy in the body. Deoxyhaemoglobin is a paramagnetic molecule that creates an inhomogeneous magnetic field in its immediate vicinity that increases T2; a tissue can be characterized by two different relaxation times – T1 and T2, at rest, tissues use substantial fraction of the blood flowing through the capillaries so venous blood contains an almost equal mix of oxyhaemoglobin and deoxyhaemoglobin. During exercise or through discomfort, however when the metabolism is increased, more oxygen is needed and hence more is extracted from the capillaries. The brain is very sensitive to low concentrations of oxyhaemoglobin and therefore the cerebral vascular system increases blood flow to the activated area. What these processes of vulnerability allow us to uncover with our body and brain, is just how profound the absence of sound can be an integral part of reconfiguring our nervous system. Something as simple as low frequencies can be our building blocks to getting there, as one research paper in 2022 surrounding speakers underscores with undetectable very-low frequencies at live concerts. As humans our audio spectrum range spans from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz( hertz), this range is our capacity to hear sound. What researchers of this paper discovered was that these low undetectable frequencies actually increase individuals to dance more. As low pitches confer advantages in perception and movement timing, and elicit stronger neural response. Researchers had individuals provide consent to have motions capturing marker headbands on their head. During the concert, the speakers only (low frequency or what they called: VLF) would be turned off and on, this resulted with more motions to dance in the low range ( 8-30 Hz they tested) Where the participants experienced a pleasurable urge to move. A large number of neurons began firing exactly in sync with the beat, which resembled the low frequencies that were played, training the neurons in their brain to match to that rhythm. This suggested low frequency sounds shape neural representation of the cortical level by boosting selective neural locking in our brain to a beat. In other words researchers are starting to realize that the sounds we can't hear—or struggle to hear—can have a greater impact on us than the ones we can. While silence alone isn't the key to improving our listening, it is an important first step in reconnecting with our nervous system. In fact some silence is detrimental and being exposed to it for too long can harm you. “You can’t change anything with silence” is what Allyson Felix, one of the most decorated athletes in history: a six-time Olympic gold medal winner and an 11-time world champion, said in her 2019 article in the New York Times. Allyson's experience of silence reached a breaking point, she wasn’t enduring the status quo around maternity. Where athlete mothers were punished for their pregnancy. She provoked huge changes by breaking her silence, forcing big brands like Nike who sponsor female athletes and others to change female athlete’s rights surrounding pregnancy. As a mother, she continues to grow and has learned that being kind to her body needs to be her ultimate priority. “Now that I’ve been in this sport for so long, taking care of my body is number one. I place such high importance on that, listening to my body” she shares in an interview. The process of listening, much like the performance of elite athletes, is not about striving for perfection or controlling every aspect of our environment. Instead, it is about learning to work within discomfort, embracing imperfection, and trusting our ability to respond effectively to what we cannot always control. Wyomia Tyus's story exemplifies how success comes not from eliminating external pressures, but from understanding and adapting to them—listening to one’s body, finding balance within chaos, and performing under pressure. Similarly, effective listening is not about perfect conditions or flawless execution; it’s about accepting the discomfort of imperfection and allowing ourselves to truly engage with what is being communicated, both through sound and silence. As we move beyond the mechanical act of hearing, we can begin to refine our listening skills by embracing the challenges that arise from external noise, internal distractions, and emotional discomfort. Just as athletes train to optimize their response to their own physical limits, we too can train our minds to be more present, resilient, and adaptable in our listening, recognizing that it is through imperfection that we unlock deeper understanding and connection.

Neuroscience of Listening and Empathy

Neuroscientist and Author Dawna Markova

Understanding the neural mechanism at play with our emotions provides valuable insights into the foundation of our ability to share and have empathy. The initial placement of neurons are similar for all human brains, the connections among them the synapses, where neurons connect and communicate with each other, numbers in the trillions are designed to change radically. Which they do throughout our life, in response to our experiences. A misguided belief we cling on to and that I’m also guilty of; is this notion that we are all the same therefore we use our listening and our attention the same way. But that’s far from the truth, as each wave synaptic change alters the way we experience things. The way we experience things shape our biological matter, and those biological changes shape the way we experience things subsequently. In other words, changes in the brain structure make that way of experiencing things more available, more probable, on future occasions. This can take the form of a self-reinforcing perception, an expectancy, a budding interpretation, a recurring wish, a familiar emotional reaction, a consolidating belief or a conscious memory. They’re all different forms of “permanence” of the way brain patterns settle into place, so that traces of the past can shape the present. What can be described as a feedback loop. Adversity Childhood Experience (ACE) influences the shape of these feedback loops. Which was first studied and popularized by obesity clinical doctor, Dr Vincent Felitti. In 1991 one of his female patients weighed 408 pounds, Felitti helped her drop down to 132 pounds within fifty two weeks, but less than a month of the transformation she gained back 37 pounds. Felitti probed his patient to discover that she had been sexually abused by her grandfather in the past. Felitti saw a repeated pattern with his other patients and wanted to study what was happening and began asking additional patients in his clinic about their childhood history. Marc Hauser’s book: Vulnerable Minds, details how Felitti was mocked when he went to the professional conference on eating disorders to reveal his findings. He was laughed at for not seeing his patients' failures and making up false realities for being overweight. But in this conference he would also meet Dr. David Williamson who worked for Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Together they would create one of the most ground breaking questionnaires to help shape health care that developed what is called: ACE score. Which would reveal the long term impacts of childhood trauma on health and well-being of an individual. Neuroscientist and Author Dawna Markova, known for her research in the field of learning and perception, particularly in “attention”, is a marvelous woman. Her childhood experience would have garnered a high ACE score, as she is a child who was abused at home by her father, neglected and later in her teens was sexually assaulted. All these collective experiences would be oblivious to me when I came across her work, one day waiting for a friend. Her and her daughter in law's book; Reconcilable Differences, would drastically change my own reinforcing perception that I held about all of us using attention and listening the same way. For the majority of my childhood I was always able to spend several hours drawing things, I never knew why, but I would waste time completing my drawings. In the process would continue being mediocre and sometimes failing in reading and writing. But I had great auditory memory and would listen in class and this only helped me through half of the test I took. Struggling to be like everyone else's reading level I concluded that perhaps I’m never going to be good at english. Dawna’s work around attention came from discovering a Qb test computer machine, that measures electrical activity in the brain, a computer-administered Quantified Behavioural Task (QBT) with a high-resolution motion tracking system that uses an infrared camera to follow a reflective marker that is attached to a headband, at Columbia University, monitoring different attention states in the brain, while she was also interning at a Harlem school that was under-resourced that deemed most of the children with learning disabilities. A term I heard too often in my childhood, when someone doesn’t fit into a mold that society has deemed acceptable. Markova had a passion for teaching what she calls; “the unteachable”, she would work with these children in the morning and later head to Columbia to work in the lab. She eventually convinced her lab to let her bring the Qb test machine to the school.

The different waves of attention

Alpha waves:

Are a medium-frequency pattern of brain activity associated with restful and meditative states. These waves measure between 8 and 12 Hz, indicating the brain is active but relaxed

Beta waves:

Are high-frequency, low-amplitude brain waves that are commonly observed in an awakened state. They are involved in conscious thought and logical thinking, and tend to have a stimulating effect.

Theta waves:

The term theta refers to frequency components in the 4–7 Hz range, regardless of their source. Cortical theta is observed frequently in young children.[14] In older children and adults, it tends to appear during meditative, drowsy, hypnotic or sleeping states, but not during the deepest stages of sleep.

Her work demonstrated to me why I was able to sit with images for a prolonged period of time, why I felt better listening to new information and as to why my physical body needed movement to access new ideas and wonder. But most prominently, it taught me the unique pathways for understanding these differences is crucial to improving our listening. Markova's work on attention highlights the importance of recognizing that not everyone uses attention the same way, and similarly, not everyone listens in the same way. While attention and listening are two separate entities that operate interchangeably between two separate parts of the brain, her research explains that when two individuals are trying to listen to each other, their brains are also operating or processing the listening they are doing, differently. For example one individual can be sorting, while the other can be in a curious phase. While both might be listening, they can simultaneously (unintentionally) not be understanding each other because of their own innate pathway with listening. That realization was so profound and sincere because it finally provided clarity for how understanding works. As Markova explains in her book this way: Each person needs different kinds of thinking to “understand”. We call these particular ways of understanding thinking talents. Which are indigenous to you, a natural preference that energizes you. Markova defines understanding as away; to soften the heart and strengthen your intellect. She shares with us that understanding happens when both parties have curiosity present. Just a little bit alone can mean a lot for misunderstanding, but when even one or both parties are lacking curiosity, it creates the tension of that friction to last longer. Her development of thinking talents allows individuals to know exactly what to ask for to be understood. As she shares in her book; “in our professional psychological training, our attention was continually directed toward what was wrong with people. Obviously this didn’t help us discover how to grow health and sanity within and between people. It is no surprise, therefore, that self criticism has become the norm”. Their book underlines the process in which you see someone else's language for understanding through their thinking patterns. Rather than to rely on our habitual attempt to convince another person to see things using our language of understanding. Which is not a simple first step to acknowledge in a conversation. Her work would be the foundation and the backbone to diving deeper in helping me develop a platform centered around having a larger dialog in the form of an interview with black creatives and scholars.

The goal of this platform would be to create an experience where a black creative can explore an internal dialog using their thinking talent. By designing questions that fit their understanding. Getting them to a place very quickly to feel comfortable with a discussion surrounding their thinking and ultimately their feelings. The first negotiation in conversation is really a negotiation with ourselves to move from being focused on what is right, and instead to getting curious about why we see it that way, a framework and mindset we approach with each interview. The purpose of this platform was to incorporate what we were learning about listening into a collaborative process, to help create an audio experience that could shape and regulate the listener's emotion. We call these audio experiences: “lessons”, the combination of three audio experiences using Embodied Music Cognition Theory and Critical Race Theory and their lived experience as an audio. I would exclude the audio holding our voice from the interview by capturing the frequency of only their voice. In a way we were manipulating them and also the listeners. We used their way of listening to connect with themselves, to make conflict about their internal dialog a real discussion, an inmate one, an honest one and curious one. I asked Markova whether being able to understand someone in this way, or how she was able to help children was a form of manipulation? Does being able to listen to ourselves mean we have to manipulate ourselves from within? What she shared with me was this: “I was manipulating the materials, the environment, the methodology, all of that is true, was I manipulating Jerome because I was effective. I don’t think so”.

What I learned was Markova had an incredible life and had gone through a tumultuous journey of healing and forgiving her father. As someone who was wounded for so long, she broke the cycle of violence and trauma for her life and her son. Now as grandmother her wisdom is shared in a different way. Through the resonance of a drum, a glimmering drum, not just any drum. Grandmothers hold a unique spiritual vibration to bring us closer to listen. They often set a rhythm of the family, keeping everyone in sync with traditions, routines and values. Much like the drum, their presence can be felt way before they are seen, lively and excited to share stories and express the love with enthusiasm. It is as if it was demanded but not aggressively, like a steel pan drum. A drum with a long history and a rough origin. Hammered into the shiny metal surface is a series of dents, each one creates a different note, subtly different from the ones around it, according to their position and size. Birth out of Trinidadian street music. When French slave plantations arrived in Trinidad in the late 1700s they brought with them a carnival tradition and their slaves formed their own festival, fuelled by drum music. After emancipation in 1834 these celebrations became noisier and more colourful, though after disturbances in 1881 called “The Canboulay” riots the British government banned drums. When steel pans first emerged in the 1930’s out of oil tanks they were not taken seriously. The instruments and their creators were looked down on by the upper class of Trinidad society because they were made and played by people in ghettos and gangs. Time and exposure eventually eroded this stigma and the steel pan is now the national instrument of the republic of Trinidad and Tobago. Such as grandmothers, there is always a joyful experience around their presence and shine. When I first implemented Markova’s work into our platform it wasn’t well accepted, but I knew it was the right framework for what we wanted to do with listening. When it comes to listening things always start bad before they become good.

Listening and Control

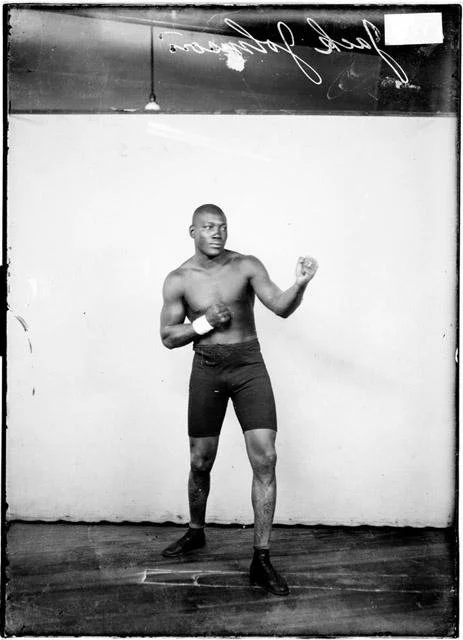

Jack Johnson 1909 Chicago ( 1878 - 1946)